Minnesota screens out 66% of child abuse complaints overall, but 4 MN counties screen out 90%. The only good thing to say about conditions in Virginia is that there seems to be some transparency in the reporting which one would hope will lead to more concern for abused and neglected children. All this talk about how we value children in America seems to be just talk.

Minnesota screens out 66% of child abuse complaints overall, but 4 MN counties screen out 90%. The only good thing to say about conditions in Virginia is that there seems to be some transparency in the reporting which one would hope will lead to more concern for abused and neglected children. All this talk about how we value children in America seems to be just talk.

Connecticut DCF Vows to Investigate After 9 Child Deaths This Year Milford, Connecticut June 22, 2014

Following the deaths of nine children this year who had been placed with families involved with Connecticut’s Department of Children and Families, an investigation is being called for. All of the deaths are reportedly caused by something other than natural causes.

KIDS AT RISK ACTION (501(c)3 non-profit, is partnering with Minnesota Public Television (TPT) to tell the INVISIBLE CHILDREN’s story through compelling interviews with children and adults within the world of child protection.

6 million children are reported to child protection services in the U.S. each year (60,000 in MN alone) Only a fraction of these children receive the help they need to lead productive lives. Help KARA change this.

Gary A. Harki

The Virginian-Pilot

©

When a call comes in to a state or local child abuse hotline, chances are it will never be investigated.

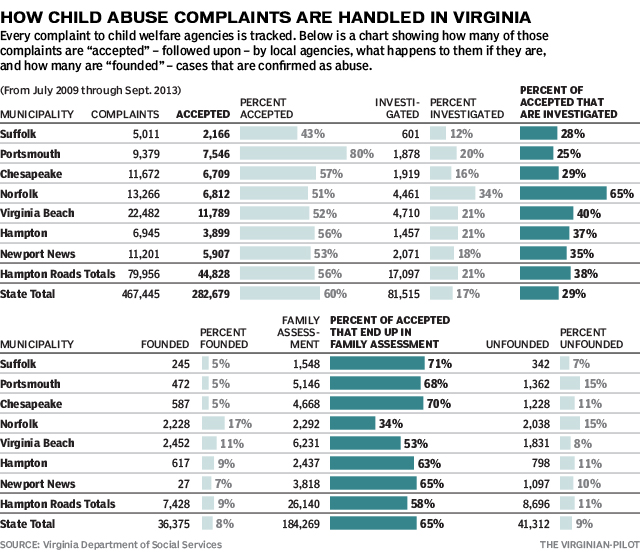

A Virginian-Pilot analysis shows that of the 80,000 complaints to Hampton Roads social services departments in a recent four-year stretch, only 21 percent were investigated. Statewide, the number was even lower: 17 percent.

Records show that the more cases social workers investigate, the more often they find abuse. But many complaints end up on a track that provides services or training, instead of an inquiry into the allegations.

In some cases, the system winds up leaving children in the care of their abusers.

The only time agencies should not investigate a call is when the allegations, if true, would not constitute child abuse, said John Mattingly, former New York City Administration for Child Services commissioner and current leader of the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Child Welfare Strategy Group.

____

Database | Child abuse deaths in Hampton Roads

____

“What you have going on in Virginia is a system that is just trying to keep its head above water,” said Mattingly, who reviewed the state data provided to him by The Pilot.

When a complaint is made, either directly to a Child Protective Services office or to a hotline, the information first is sent to the CPS office in the city where the abuse allegedly occurred. Each city runs its own CPS office; the state plays only a supervisory role.

The local office then must decide whether to follow up on, or “accept,” the complaint. That decision is supposed to be based on state guidelines for what constitutes abuse and neglect.

In Virginia, 40 percent of complaints are never followed up on by CPS workers.

Of those that are accepted, most wind up in “family assessment,” meaning social workers visit the family but do not take steps to set up a formal case. Some examples of those complaints: “minor physical injury,” prenatal substance exposure, lack of supervision, mental abuse/neglect, and a lack of food, clothing or shelter.

More serious cases are routed to investigation, in which social workers determine whether the complaint is “founded” – which means there is actual abuse. If so, they can take action, including removing a child from the home.

Cities could investigate every case if they chose to, said Mary Walter, child protective services policy specialist with the state Department of Social Services. Money and resources are limited, however.

Virginia has no guidelines for what percentage of calls should be accepted or investigated. Nationwide, 70 percent of calls are generally expected to be serious enough to be accepted, Mattingly said.

The percentage of complaints that turn out to be actual child abuse varies greatly from city to city, indicating that municipalities might be responding to calls differently. But according to Mattingly, cities are required by federal law to follow the same guidelines.

“The validity criteria is the same throughout the state,” Walter said. “I don’t have an answer for that.”

From July 2009 through September 2013, Norfolk accepted only 51 percent of complaints, below the state average of 60 percent, but investigated more than anywhere else in Hampton Roads: 34 percent – double the state average.

Norfolk tends to investigate more often because it sees more cases of abuse or neglect that include drug use and mental health problems, said Al Steward, Child Protective Services program manager.

Mattingly said Norfolk appears to be rejecting some complaints to keep its caseloads manageable: “I think that is unconscionable.”

A spokeswoman for the city’s Department of Human Services declined to comment.

In Portsmouth, social workers accept 80 percent of complaints, but 68 percent of those end up as family assessments.

The city would not grant an interview with a representative from social services. In an email, a spokesperson said: “There are times when it proves as beneficial to the family and the department to have a family assessment instituted instead of an investigation.”

It’s the state’s responsibility to make sure all calls are handled essentially the same, Mattingly said.

“The No. 1 principle is,” he said, “the state should be responsible for seeing to it that a child doesn’t get different treatment just because of where she lives.”

He said that doesn’t appear to be happening in Virginia.

Pilot database producer Jon Davenport contributed to this report.

Gary Harki, 757-446-2370, [email protected]

Gabriella Souza, 757-222-5117, [email protected]

Few complaints to child abuse hotline investigated